I was in a Barnes and Noble bookstore not long ago and wandered into the children’s section. In one corner was a toy train table with wooden tracks and colorful train cars attached to one another magnetically. Engrossed in play were a mom and her 4 or 5 year-old son. I stopped to watch, remembering my kids’ love of trains at that age.

I was in a Barnes and Noble bookstore not long ago and wandered into the children’s section. In one corner was a toy train table with wooden tracks and colorful train cars attached to one another magnetically. Engrossed in play were a mom and her 4 or 5 year-old son. I stopped to watch, remembering my kids’ love of trains at that age.

The boy was creating a long line of train cars to pull around the track when his mother picked up another car and had it ask, “Can I join your train?” “No, we’re full,” the boy answered for the long train. “I think there’s still room,” the lone train car returned. “I said no,” the boy stated emphatically. “Well, I feel left out and that makes me mad!” The mother was still using her train’s pretend voice. The boy stopped playing briefly and looked into his mother’s eyes after this strong sentiment. She gazed at him evenly to reaffirm that she didn’t say it, her train did. “Well, maybe you can join us in five minutes,” the boy offered as his train pulled out of the station.

I wasn’t sure exactly what was taking place here, but it seemed likely that the effect of this train play was to coach the boy on words to use when he felt angry or left out. This interchange reminded me of what psychologist John Gottman calls emotion coaching. In The Heart of Parenting: Raising an Emotionally Intelligent Child. he describes 5 steps to emotion coaching, which isn’t necessarily done while playing trains, but more often during one-on-one exchanges:

1. Become aware of the child’s emotion.

2. Recognize the emotion as an opportunity for intimacy and teaching.

3. Listen empathetically, validating the child’s feelings.

4. Help the child find words to label the emotion he is having.

5. Explore strategies to solve the problem at hand.

Gottman’s research shows that children whose parents use emotion coaching with them, are more resilient and better able to regulate their emotions. It’s likely that because these kids aren’t using as much energy to manage their daily emotional ups and downs, they have more energy available to focus on school and social relationships. In Gottman’s research emotion-coached kids did better in school and friendships than un-coached children.

Preliminary findings by additional researchers suggest that people with low emotional intelligence have higher rates of substance abuse later in life.

Often simply helping a tearful child identify whether he’s more sad or more frustrated can have a calming effect. Kids know you are hearing them and trying to understand their experience. After they settle down some, they are more ready to problem-solve, but Gottman encourages us not to jump in with suggestions. He wants us to coach our kids to come up with their own problem-solving strategies using questions such as, “What do you think you’ll do next?”

This is the part that I have the hardest time with — letting my kids generate their own solutions. It is so challenging for me to sit there and be patient with an upset child and gently coach her to think of what, let’s be honest, are often barely workable solutions! Meanwhile I, older and a bit wiser, have maybe 4 or 5 ideas on the tip of my tongue which could quickly solve the problem.

Once the child decides which of her options she wants to try first, then we still have to keep our mouths shut and be supportive. Again, being a grown-up, I know the initial not-so-great idea likely won’t work out. And it can all take such a long time! It’s a little excruciating, especially because I usually have to be somewhere soon. It’s probably good I didn’t go into teaching.

However, I do want to get better at this aspect of parenting. I believe Gottman’s advice is valid. And in Raising Cain: Protecting the Emotional Life of Boys, Dan Kindlon and Michael Thompson emphasize that learning emotional literacy is especially important for boys. Unlike girls who tend to use emotional language in their play and notice the feelings of those around them, young boys in Western culture are generally taught to suppress their emotions (except anger). Boys are regularly steered away from focusing on their inner world or the emotional cues of others. Kindlon and Thompson suggest that teaching boys an emotional vocabulary allows them to express themselves in ways other than anger and aggression.

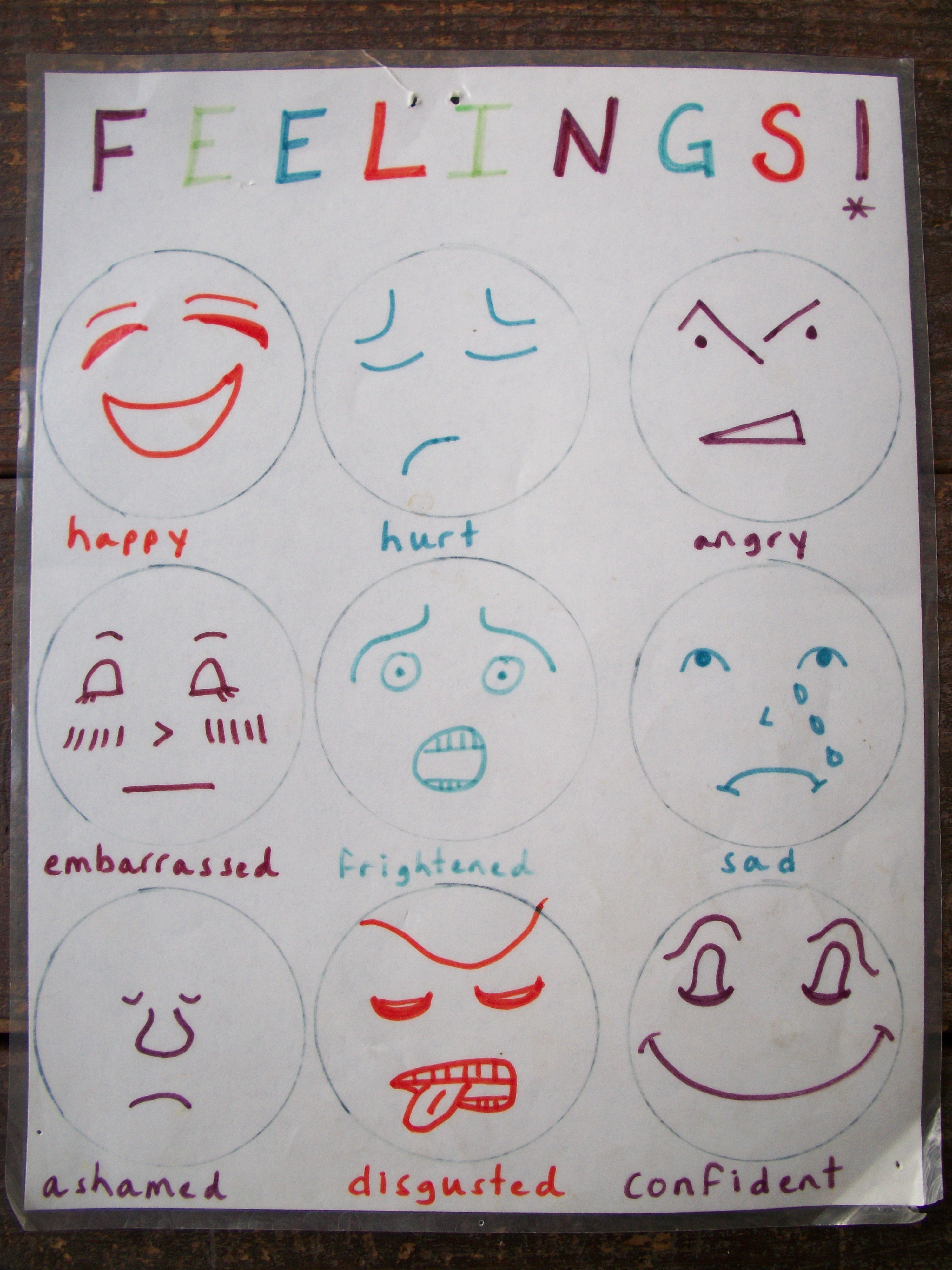

I have found that with young children, using Feelings Charts or posters (with numerous cartoon or real faces showing various emotions) can be surprisingly helpful.

When I did play therapy as a psychologist I used to bring small laminated Feelings Charts into our play time. I’d often have a toy we were using land on the Feeling Chart face in order to help the child learn that emotion. When my own kids were upset as toddlers and preschoolers, I’d have them point to how they were feeling on the Feelings Chart and 9 out of 10 times that simple action helped them begin to calm themselves.

But I do admit it can be hard to “let our kids express their feelings” in public. Especially those intense emotional spells that happen between ages 2 and 5! My son Stephen was very attached to his grandparents when he was young, although they all lived far away and could only visit for short periods. When it was time to say goodbye, Stephen would accompany us to the shuttle that took his grandparents to the airport. He’d begin to cry as we spotted the shuttle driving up, and then stand there bawling and waving to his grandparents as they boarded the shuttle bus.

Todd worried that letting him do this would mean Stephen would be an emotional wreck for the rest of the day. “Couldn’t we keep him home and avoid a scene,” Todd asked. I felt fairly awkward as strangers stared out the shuttle window at my sad little boy who kept crying harder as we waited. But Stephen always wanted to stay until the shuttle left and it seemed fair to grant him this small request.

Stephen’s grandma told us that after one of these times, as she retrieved something from her overhead bag, she saw that half the passengers who’d witnessed Stephen’s goodbye had tears in their own eyes and were smiling understandingly.

And here’s the unexpected part: We’d bundle our crying child back into our car and talk about how sad he was, but also remind him that he would slowly feel better. Then we’d discuss our plans for the day. By the time we arrived home a mere 20 minutes later, Stephen was mostly himself again. Each time he got through the intense emotion, not stuck in it, as we’d worried. This was one of our first lessons in emotion coaching, and in the end it wasn’t as hard as we’d dreaded.

Other ways to teach kids emotional intelligence? Leave a comment!

Sweet Spots: Helping Your Kids Find ENOUGH in Their Lives.

Sweet Spots: Helping Your Kids Find ENOUGH in Their Lives.

You might be interested in the Institute of HeartMath’s Heart Smarts programs used in over 400 school systems in the US. There are programs for teachers, administrators and children. Take a look at the case studies to see some amazing result achieved in the area of reading and math test taking, peer support, and more